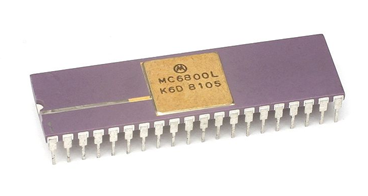

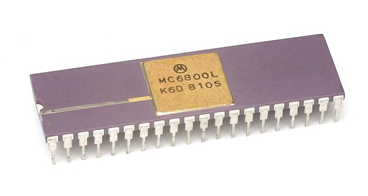

It’s easy to get lost in the dizzying pace of modern computing, where processors boast billions of transistors and clock speeds that dwarf anything imaginable just a few decades ago. However, there are times when it is worthwhile to appreciate the pioneers who laid the groundwork and paved the way. The Motorola 6800 microprocessor is one such unsung hero, quietly marking its territory in computing history. Released around 1974, the 6800 arrived on the scene almost concurrently with Intel’s 8080, sparking a quiet revolution in the world of 8-bit computing. Imagine a time when 8-bit was revolutionary! This little chip, housed in a familiar DIP40 socket, was a significant step forward. It had a 16-bit address bus, which allowed it to access 64 KB of memory, a significant amount of space. That was a significant playground for processors of the time, just for context.

What caused the 6800 to run? By today’s standards, it wasn’t exactly overflowing with registers. It had an index register (IX) that was very useful for addressing memory and two accumulators (ACCA and ACCB) that held data during operations. However, the 6800 lacked dedicated input/output (I/O) instructions, which is an intriguing flaw. Memory-mapped I/O had to be used instead in systems built around it. As a clever workaround that demonstrated the adaptability of early system designers, this meant that I/O devices were treated as if they were memory locations. A whole family of processors was built on this architectural choice, which also has a robust instruction set and interrupt handling capabilities.

The 6800 wasn’t just a standalone chip; it was the progenitor of the 680x series, a lineage that included microcontrollers and microprocessors, some of which, remarkably, are still in production today. Consider that for a moment: a design from the middle of the 1970s still has an impact on technology today. The 6800 treated program, data, and stack memories as a single space with a 64 KB limit, according to its architecture. Even though branches were somewhat constrained in their immediate reach, program execution could jump almost anywhere. The stack, which is essential for temporary storage during function calls and interruptions, can also be placed flexibly. Data can be stored anywhere. IRQ (maskable), NMI (non-maskable), SWI (software), and the crucial RESET vector were all handled by pointers in the reserved memory locations at the top of the address space (FFF8h to FFFFh). One important feature was interruptions.

The ability to mask or unmask the IRQ interrupt made it possible to gracefully deal with events from outside the system. However, the NMI was non-negotiable and could not be disabled in order to guarantee that critical system events would always be acknowledged. A software-driven method for initiating interrupt routines was provided by the SWI, which could be invoked directly from the program. Before jumping to the appropriate handler, the processor meticulously saved its current state—the program counter, registers, and flags—on the stack. A specific RTI (Return from Interrupt) instruction then brought it back. The data movement, arithmetic, logic operations, and control flow sections of the instruction set consisted of 72 distinct instructions.

The foundations for complex programming were addressed modes like implied, accumulator, and immediate. It is fascinating to observe how these fundamental operations and architectural choices enabled the development of complex systems. This chip was not just made by Motorola; second-sourcing by companies like AMI and Fairchild made the 6800 even more influential. It competed head-to-head with competitors like the Intel 8080, each with its own advantages and tenets. While the 6800 carved out its niche with its elegant memory-mapped I/O and its foundational role in a powerful processor family, the 8080 may have boasted higher clock speeds or additional I/O ports in some iterations.

We can see the development by looking at its successors, like the 6809. For instance, the 6809 maintained the 8-bit core and the 2 MHz speed while also adhering to the 64 KB RAM limit and lacking dedicated I/O ports. However, it introduced new registers and a more advanced instruction set. It was a clear step up from the 6800 and built on its legacy. Despite the fact that the silicon marvels of today make the Motorola 6800 appear ancient, its impact is undeniable. It was a workhorse and a fundamental piece of technology that powered numerous systems and devices. Today, the microcontrollers and processors that shape our digital world continue to carry its legacy. It is evidence of careful engineering and the long-lasting power of an 8-bit core that has been designed well.