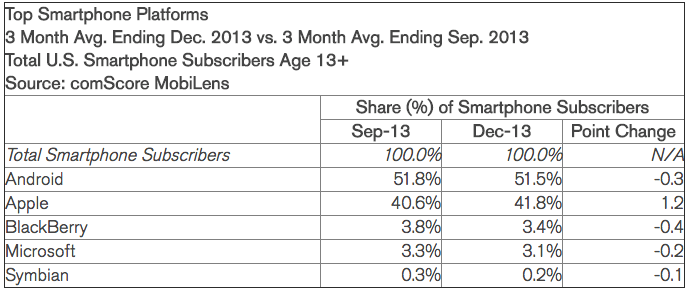

In many ways, BlackBerry was the producer of the world’s first widely-adopted premium smartphone brand. At its peak, Blackberry owned over 50% of the US and 20% of the global smartphone market, sold over 50 million devices a year, had its device referred to as the “CrackBerry”, and boasted a stock price of over $230. Today, BlackBerry has 0% share of the smartphone market and has a stock price that has hovered in the high single digits for most of the past few years. How did BlackBerry fall from such soaring heights?

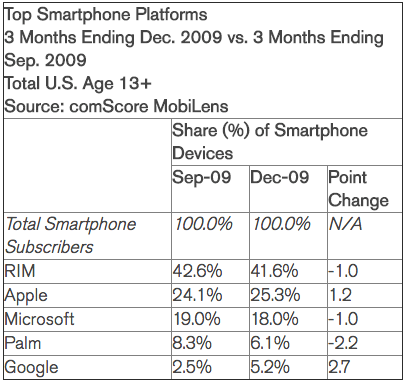

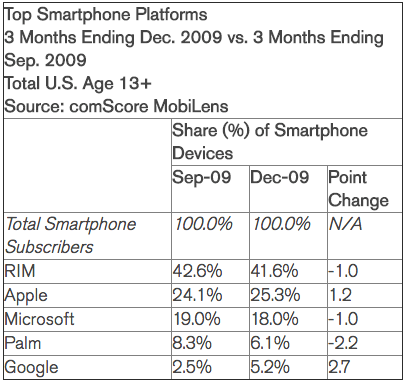

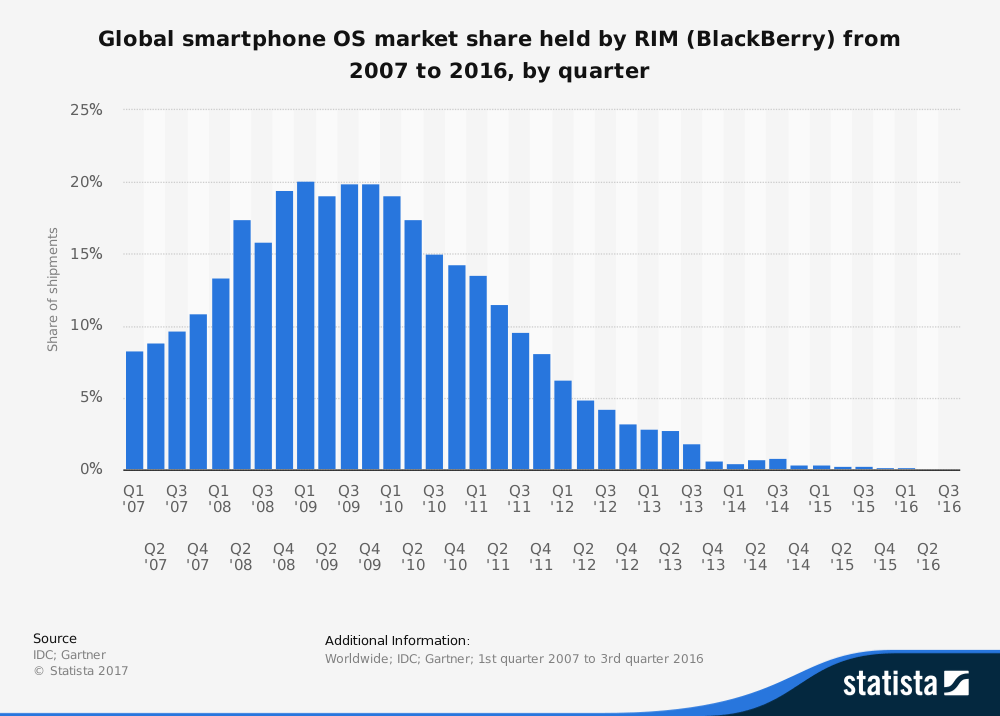

First, a little bit of history. BlackBerry was founded in 1984 (as Research in Motion) and was originally a developer of connectivity technology like modems and pagers. In 2000, the company introduced its first mobile phone product in the BlackBerry 957, which came with functionality for push email and internet. Over the ensuing decade, the BlackBerry became the device of choice in corporate America due to its enterprise-level security and business functionality. Even after the competitive entry of the iPhone in 2007 and Google’s Android OS in 2008, BlackBerry was certainly not destined for failure. In fact, BlackBerry continued to dominate the smartphone market through 2010, when it still held over 40% of domestic and nearly 20% of global market share.

Ultimately, however, it was a combination of slow market reactions, focusing on the wrong end market, misunderstanding the smartphone’s value proposition, and poor execution that sealed BlackBerry’s fate.

Slow market reaction to competition. BlackBerry’s leadership initially dismissed Apple’s touchscreen iPhone, insisting that users preferred their physical keyboard. When the iPhone sold well, BlackBerry hastily released a touchscreen device (BlackBerry Storm), which often didn’t work properly and was met with horrendous reviews. Subsequent devices reintroduced the keyboard in a combo touchscreen-keyboard setup (e.g., BlackBerry Bold), which momentarily stemmed the tide, but would eventually prove misguided as the market continued moving toward larger screen real-estate.

Focusing on the wrong end market. As Apple and Google made smartphones accessible to the mass consumer by creating slick user interfaces and attractive apps, BlackBerry remained doggedly focused on its enterprise customers and their security and connectivity requirements. This was the traditional innovator’s dilemma at work – BlackBerry catered to its most important customers that generated most of its revenue and profits, and hence neglected the end market that would ultimately become the most important. When enterprises adopted “Bring Your Device” policies, it was no surprise that employees began replacing work BlackBerries with personal iPhones or Android phones en masse.

Misunderstanding the smartphone’s value proposition. In part due to its enterprise focus, BlackBerry innovated primarily around feature improvement – faster email, better security, etc. In doing so, it missed the value proposition of the smartphone as a platform for personal productivity and entertainment. While Apple and Google built a moat around their third-party app ecosystems, BlackBerry’s insistence on first-party development made its devices far inferior. Even its most popular app, BlackBerry Messenger (BBM), was leveraged ineffectively – by mandating that BBM be installed only on BlackBerry devices instead of building up a larger user base across platforms, BlackBerry missed the opportunity that third-party messaging apps like WhatsApp eventually took advantage of.

Poor execution. Even when it did try to adapt, BlackBerry couldn’t execute properly. The launch of the touchscreen Storm in 2008 was a colossal failure. The 2010 release of the Playbook tablet was largely derided for a lack of native email, calendar, and contacts applications. Even its more recent incarnations, like the BlackBerry Priv in 2015, suffered from ineffective product launches, poor functionality, and incoherent value propositions.

It’s not surprising that BlackBerry lost the smartphone wars. But BlackBerry’s story may have another chapter that is yet to be written. Since bringing on turnaround veteran John Chen as CEO in late 2013, BlackBerry has given up on producing phones and has reinvented itself as a software and services business. Leveraging a portfolio of enterprise security products and riding the wave of automotive innovation with its QNX system, Chen seems to have righted the ship. In its most recent quarter (Q3 2017), BlackBerry reported 7% growth in software and services and guided to 10-15% growth for the year. In the autonomous vehicle space, BlackBerry has partnered with Baidu, Nvidia, and Qualcomm to secure their software. Investors have rewarded the company – its stock price now sits around $13 per share, a level not seen since mid-2013. Though the situation looks more promising than it has for a long time, only time will tell whether BlackBerry will rise again.

[“source=digital.hbs”]