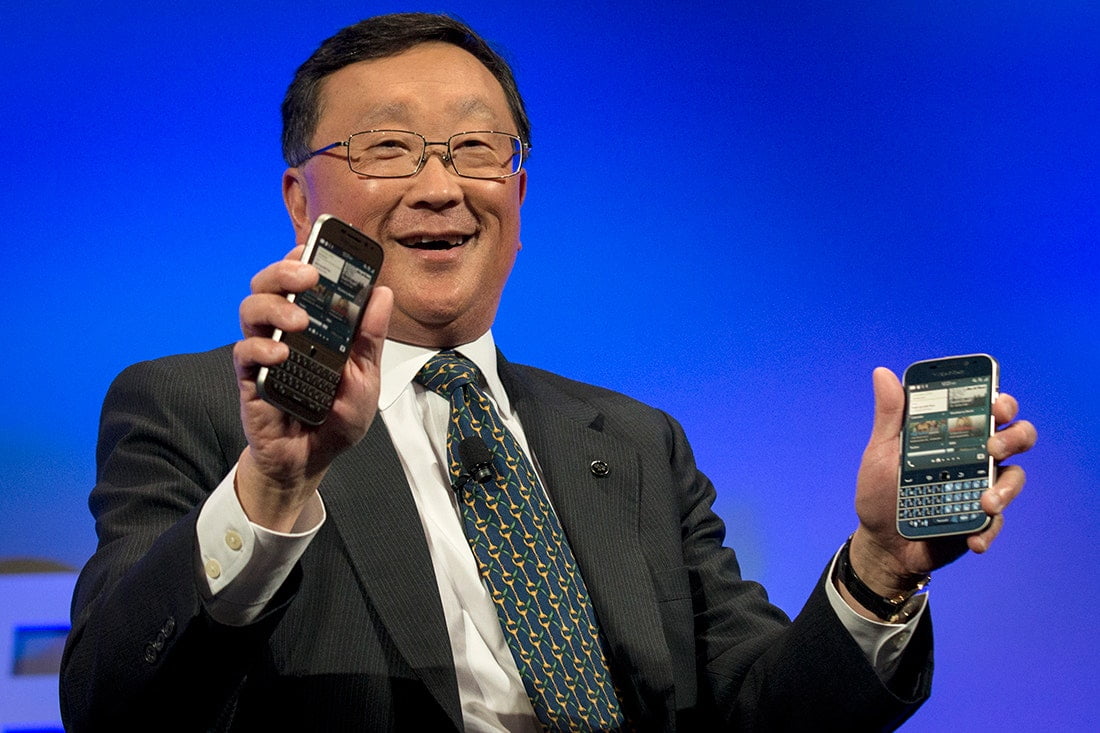

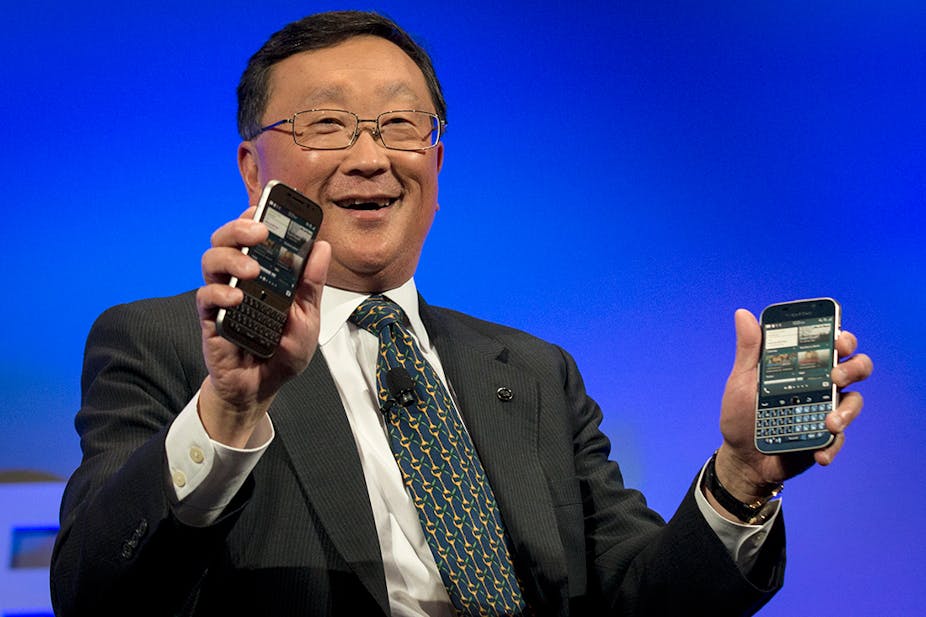

Last night, BlackBerry CEO John Chen penned a blog post on net neutrality. He was in favor of net neutrality but in the last half of his post introduced a whole new notion of neutrality: “application neutrality,” or app neutrality for short.

Suffice it to say, the internet decided this was crazy. And, I’m going to keep it real here. I agree. It is crazy. Really crazy to equate app neutrality with net neutrality.

But it is perhaps important at times like these to remind ourselves why. One of the dangers of the net neutrality debate is that the case for it can quickly fall into the trap that it is good because it’s fair. But as Scott Adams has told us, it is a word that allows morons to participate in debates. The app neutrality claim has a similar “fairness” feel about it.

So what did Chen mean when he raised the issue of “app neutrality?”

“All wireless broadband customers must have the ability to access any lawful applications and content they choose, and applications/content providers must be prohibited from discriminating based on the customer’s mobile operating system.”

He argues that BlackBerry is practicing this because it made its popular BlackBerry Messenger (BBM) an application on all mobile platforms including iOS, Android and even Windows. However, Apple, for instance, has its iMessage app only on Apple devices. In addition, Netflix hasn’t bothered to make an app for BlackBerry. That last claim is a little rich as Netflix is available on the web so is hardly kept from BlackBerry users.

Now what is going on here? BlackBerry would like to compete for Apple customers, but it knows that some key apps aren’t available. iMessage may be one constraint in that switchers would lose their messages if they moved to BlackBerry. Of course, that is the reason BBM was made widely available. The company hoped to lure consumers over so that, in the future, making a switch would be easy. When BlackBerry was the big cheese prior to 2010, BBM was locked into its system. But it is true: if apps were more widely available across platforms, it would be easier for consumers to switch among them.

We could spend some time talking about switching costs and competition. That is a relevant issue. It is why, for instance, we have mobile number portability between carriers. Switching costs can reduce competition. But even so it is a long stretch to claim that we need app neutrality. There are costs and complications in that notion that I won’t begin to get into here.

But the important thing is that it is completely different from the issues that drive net neutrality. We want net neutrality so that people who are providing content and apps have a channel to put them on – namely, the web – and they won’t face differential charges and quality of service in doing so. It will then ensure access to consumers without the possibility of price discrimination by some bottleneck provider – either a carrier or perhaps even a mobile operating system owner – in the middle.

Without such neutrality, those in the middle will have the ability to use price discrimination of some form to snare extra profits from content providers and perhaps app makers. This would reduce their incentives to develop that stuff in the first place, and the entire ecosystem would suffer. (This argument is made by me here).

Thus, in the net neutrality world, Apple is the app maker. So what we would be concerned about is BlackBerry refusing to make Apple’s iMessage available rather than the other way around. Or at least that would be the closest analogue. Instead, the app maker, Apple, has decided it does not want to make its app available to all customers. This happens all the time. For instance, Netflix does not make its content available to people unwilling to pay $8.99 a month. App makers and content providers are allowed to restrict access in a net neutrality world. Net neutrality is about protecting them not others.

So Chen was wrong to associate app neutrality with net neutrality and muddy that debate. He may have a point somewhere about switching costs but he did not present a reasoned argument. He just jumped up and down and claimed it was unfair. Crazy.

[“source=theconversation”]